Editor’s Note: This is the 28th in a series of “How I Got That Story” interviews featuring the winners of the 2005 AltWeekly Awards. First-place entries are collected in the book “Best AltWeekly Writing and Design 2005.”

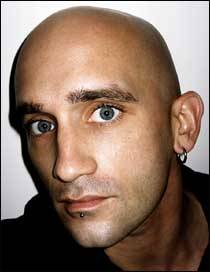

As the person responsible for designing the feature spreads that appear in the Miami New Times each week, Michael Shavalier says that, creatively speaking, some cycles are better than others. Composing more than 50 spreads per year can occasionally make it difficult to keep things fresh and avoid visual monotony or, worse still, creative cliches.

Shavalier, whose foray into the art world involved using crayons to adorn the walls of his childhood home in upstate New York, says the best layouts come together through a collaboration where text and design (as well as the people who create them) work in unison to form visual balance, each complementing the other. His spread for a story titled “Coffin Classics,” which won the 2005 AltWeekly Award for Editorial Layout, is a prime example.

Using cues from the feature story that chronicled the tension among Goth music scenesters in Miami, Shavalier employs dramatic typographic detail and minimal graphics with a combination of live-action and portrait photography. The result is a simple design that makes a strong statement without overshadowing the text.

Shavalier has worked in the art department of four New Times papers over the past eight years. Between deadlines in Miami, where he’s been art director since 2003, he spoke about why he doesn’t always read the stories he’s creating a spread for, and how flexibility is sometimes the best tool an artist can have.

How did you come up with the design concept for your award-winning spread?

This one happened to work through photography. The story is about people that are thinking back to a time or era that had everything to do with mood: things they wore, how they dressed, how they carried themselves. The visual stage was somewhat set at the first pitch, and because of the nature of the characters, they were easy to work with. It wasn’t like going out and shooting politicians; it was much more organic. Goth people are interesting, they’re Victorian-like, so immediately I started thinking in terms of graphics and type in that direction. The finer points came as I was designing.

How were you able to construct such a strong visual aesthetic by using such a minimalist style?

My design has changed over the years, particularly working for New Times. I went to college and learned design through the grunge-type era. Magazines like Raygun, Bikini, huH and Speak, and designers such as David Carson, Christopher Ashworth, Martin Venezky and Scott Clum had a heavy influence on me then. The way they handled typography was dirty, rough and beautiful at the same time. It was the first time I saw what type could be. It was “fine art” and I loved it.

I still look back at good designs from that era, and they hold up. Part of the fight is knowing when to under-design and let photos and stories and headlines speak for themselves, or when to over-design because those elements aren’t enough. For this one, I felt like the photos were giving so much information and were so compelling that they pretty much could hold the pages themselves. At that point it was a matter of basically giving it an overall look and bringing it all together.

What made you decide to combine the studio shots with the on-location shots?

What I was trying to convey is the real crux of the story, these people who remember when they were Goth and how great it was, and how the Goth scene today is not the Goth scene of yesterday. I felt that the only way to really show that was mixing these very quiet, artistic studio shots of these older Goths with shots of the modern, drinking, club-going scene of today. If you really look at those photos, you see the differences. You can almost imagine some quiet music playing in the background of the studio photos, and then you look at these women in these bustiers drinking beer in the club, and it’s different. Sometimes the visuals are the best comparison or contradiction.

Do you find that you typically stick to the creative vision that you initially have for most projects?

No. On a lot of these stories, the biggest asset is the ability to be flexible. Things in your head sometimes play out differently when you get in a room and try to produce them. There have been times when we scrapped an entire shoot or entire illustration at the last minute because it just wasn’t working. I think if you’re not able to be flexible like that — especially on these deadlines for a weekly — you’re not allowing yourself to have the most successful image or product. You have to put aside what you may want for what is best.

Would you say that’s one of the biggest challenges for a designer?

I think it’s that and also the amount of work. The art directors of this company put out 52 covers per year, so those of us who have been around for more than a couple of years have put out hundreds of covers. After a while you start to see not similar stories but similar themes come up. Sometimes you’ve got to sit back and go, "Okay, I know I’ve done something like this before, what makes this one different?" because obviously it’s different.

Do you always read a story in its entirety before you begin designing?

Knowing the story helps. Sometimes knowing too much about the story hurts because you get into so many finer details that the reader is not going to know until they get far into a story. Sometimes I actually stop myself from reading all the way through because if I do, then I know more than that person is going to know when they open that page. I try to approach it in my mind as, "What would I want to know, what would I need to know, and what would be too much information for me when I look at this or when I look at the cover?" I try to start to build the idea from there.

How does working mostly in grayscale affect your design pursuits?

It took some adjusting when I first started. In my mind, the strengths in a black and white are balance and positioning. Typography is key, and the images need to be really arresting and sometimes graphic. There are certain types of style that work really well on newsprint, and I’ve found myself over the years adjusting my style to the benefits. There are certain things you can do and not have to worry about cleaning it up like you would if you were printing out a glossy where someone is going to notice every little blemish. Sometimes in a photo the colors are too busy and when you knock it down to black and white, it makes a stronger image.

How does working at an alt-weekly influence your craft?

The one thing about weeklies is our readership is so vast. If you’re designing for a men’s magazine or a specialty publication, your readers vary but they’re not as diverse. I try to design in a way that can open up a story to different sorts of readers. We have to try to stay hip but at the same time not scare off the older readers. You can’t grunge everything up because they’re not going to want to read it.

Trying to find the balance is sometimes hard. I have my New Times style of design as I call it. It’s different from how I would design outside of here because I have to be able to communicate to a large group of readers. Sometimes I dial it back a little bit — consciously. I think, “Well, I’d really like to do this, but it might be a little too experimental.” If it was a bunch of designers looking at it, that would be different.

What elements constitute good editorial design?

You’ve really got to have a handle on typography. There’s an inherent beauty to type and how it works with image and how it works on a page and communicates. Type is a major, major factor. Image selection is also important. There are so many photos you go through, so many illustrations you commission, and knowing the right one for the right story, picking the right style and the right artist, is key.

Do you have a file of good examples that you harvest ideas from?

Three of the four walls in my office are just covered with stuff. Things I find printed, cards I get from illustrators, posters — anything that I look at and I think, "Wow, that’s a really cool image or really interesting way to communicate visually." It’s not really borrowing ideas, but jogging your mind. Sometimes I just need stuff around me to make me think, "Wait a minute. Why am I doing it that way?"

Joy Howard is a freelance writer living in Amherst, Mass. A 2003 fellow of the Academy for Alternative Journalism, she has written for Boston’s Weekly Dig, Cleveland Free Times and the San AANtonio Convention Daily.